Chapter VIII: "SAIREY GAMP" AGAIN.

"The old wife has spoken her oracles." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XV.

The midwife, the old Hajjia, now became a test of our politeness, for she arrived at all times and seasons, and though we felt constrained to brew tea for her and to have sweets ready for her grandchildren, I did not feel bound to lend her my whole attention, but wrote letters when I wished, or typed out notes on my small machine. This she viewed with interest. It was not so much talk that she needed as contemplation of my various activities.

"A lady from Mosul came here to Baashika once, and she and I were much together, just as you and I are. Wallah, I brought my bed and slept in her room."

I looked at her with apprehension. Her presence was always a little malodorous, and her conversation exclusively obstetrical in theme. I shuddered to think of those wrinkled and grimy hands at their work.

On the morning of April the thirteenth she arrived betimes, fully determined to be my "other sister" all day. I was busy turning out things from my suitcase, and she sat in my bedroom watching closely with her old eyes, and would have examined everything piece by piece had she dared. When Rashid arrived to take me, as he had offered, to Tell Billa, her eyes goggled when I said to him that I had a parcel for his wife. We started off all three together, and on the way she possessed herself of the parcel and opened it to see what it contained.

[71]

Rashid's young wife was delighted with the length

of silk I had brought as a present for the feast, and

smoothed the material with appreciative fingers. Then

we set off to the mound, Rashid, Sairey and I — the

old woman more than ever determined not to let

me out of her sight. We went by way of Shaikh Muhammad,

and encountered there the guardian, a

kochek, a gentle old man with a white beard, dressed in

spotless white. He inquired whether I would care to

visit the tomb, but I thanked him and said we would

return another day.

"There was a man who made himself out to be a shaikh. He was not a shaikh, but he made himself out to be one. He came and he sat by the bridge by Shaikh Muhammad, and he called, and a snake came out towards him. It came to him and it bit him. He boasted, "I am a shaikh; it cannot harm me! From my granddad I inherit this gift — snakes cannot poison me.' But he began to swell and presently he fell down senseless. We took him to the Arab, who placed his kherza on the bite. Presently the man came to, and cried, 'What is this? What have you done?' They tried to persuade him to keep the kherza on him, but he refused and threw it from him and began to walk away. He had not gone far before he turned yellow and fell down. Yes! He, this Arab, is a good man and asks no fee, but people send him a sheep, or some such gift, as kheirât (bounty). He has a house and a garden."

Arrived at the mounds of Tell Billa, we climbed up and he showed me excavations of houses and the exploratory trenches, explained the plan of the dwellings, and pointed out the drain-holes from the houses into the narrow streets. Rashid is so unusually intelligent that I can well understand why the Americans gradually advanced him to the position of foreman and left all in his charge when they went away. We sat on a carpet of wild flowers to rest, and the old crone,

[73] who had followed silent for the most part, pointed to the fortress on the hill which we had failed to reach.

"There is the qal'a," she said. "A ruined place like this. Treasure is buried there. One night two men of Baashika went forth with mattocks and basket to dig for it. But the Reshé Shivvé came out of the qal'a and leapt on them and hurled them out of the hole they had been digging, and they were half dead with fright. They never dared to return."

At lunchtime, back in our little house, I heard sounds of arrival, and, going out, found A. in the courtyard, surrounded by her luggage. Had I not had her letter, she asked, written three days before? I had not, but I had half-expected that she might turn up for the feast and was glad to see her, for A. is of a rare kind, indeed amongst all the women in ‘Iraq I knew none that I would have asked to Baashika with less fear. I knew that she might be depended upon not to utter a tactless word or display tiresome inhibitions, nor would our picnic mode of life dismay her.

Sairey's talk about the qal'a made me determine to reach it. Its local name is Qal'at Asfar. Jiddan suggested that this time we should take a guide lest we miss the path again, so when A. had unpacked and set up her camp bed, we procured a dark, shaggy-looking lad as guide and making our way up the hills, clambered up the steep side of the ruined fortress. The rough masonry of blocks was fitted into the rock, so that at times it was difficult to tell the work of Nature and that of man apart; the whole had formed at some remote time a stronghold, and in the plateau above there was a deep well lined with masonry. Other openings on this flat surface, which looked like a terrace, were curved like the walls of a jar and looked as if they were air holes to a chamber long blocked by earth and debris. One opening was small and square. As we wandered about, [74] the shaggy-haired boy repeated the story about buried treasure and the spirits that guard it.

"We should fear," he said, "to come here at night." We returned by an easier route, and followed a rutted path in the rock which led us back by way of the shrine of Azrael to the aqueducts and the cistern above the olive-groves. Here our young guide, with another boy who had joined us on the way, left us unceremoniously, and shedding their clothes, they leapt into the water. The Pan-like creature did not even ask for a guide's fee. At the fair, some days later, he gave me a shy smile, and going to him I put some money into his hand, telling him to choose some sweetmeats.

"What shall I choose?" said he, looking at the stalls.

"Anything you like," I replied, and left him.

A little afterwards he was at my side, holding towards me a packet of Rahat Lukûm (Turkish Delight). He had hunted for me in the crowd. "But it is for you, not for me!" He was amazed, and went off with it wordless.

When we returned, the inevitable Sairey had arrived. I had already warned A. and apologized for our constant visitor. This afternoon, however, she was not alone: she had brought two daughters, one a married woman, and the other a bride. We prepared tea for them and ourselves.

This afternoon Sairey had all excuse, one of her daughters was a tattooist and she knew I was interested in the art. But that was not all: she wheedled a little, she had seen the silk that I had given to Rashid's wife, and surely I had a roll for her — was not the feast approaching? Now Sairey had at various times received money, and I had already earmarked my limited store of gifts, some of which were reserved for the visit to Shaikh ‘Adi. Regretfully, I refused, but A. immediately lightened the situation; she had brought with [75] her some charms in Hebron glass against the Evil Eye, a whole string of them in blue, black, white, and yellow, each bead representing an Eye. These proved an immediate salve, and never failed to give delight whenever and wherever she bestowed them.

We talked of tattooing. The women never admit that tattooing has a magic purpose, and tell you that they submit to the process for zîna (decoration) or hilwa (beauty). Here and there, however, marks have been tattooed to keep off pain, and the floriated cross and cross with a dot in each arm, both common designs, are undoubtedly magical and health-preserving signs. The married daughter explained how she worked. The ingredients were sheep's gall, lamp-black (from an olive-oil lamp only) and milk fresh drawn from the breast of the mother of a girl-child. If the baby is a boy, she said, the punctures would fester. The consistency of this mixture must be that of dough. A pattern is traced on the skin with this paste and then pricked in with a needle or two needles tied together with thread. These must draw blood. At first the surface swells up, but later settles down and the design appears in a deep blue. Yazidi women rarely tattoo the entire body as do the women of southern ‘Iraq, but content themselves with adorning the back of the hand, the wrist, forearm, chest, ankle, and lower leg. The favourite designs are these:

(1) The misht, or "comb". By the way, there is no hesitation in pronouncing this word, although I had always heard that it is one of the words which Yazidis will not utter because it contains the consonants sh and t, and suggests the forbidden name Shaitan (Satan). The "comb" is often joined to a circle called the qamr (full moon), or finished by a cross, sometimes plain.

(2) The cross.

(3) The gazelle. This is a conventionalized representation of the animal and is a favourite design. Those [76] that I saw had above the back of the animal a spot, called daqqayeh.

(4) The rijl al-qatai, "sand-grouse foot". This resembles the print left by a bird's foot in the sand.

(5) The moon, either full or crescent.

(6) The lâ'ibi, or "doll", a primitive outline of a human figure with extended arms and legs apart.

(7) The dulab katân, or kiûkiûukh: the spool or spindle.

(8) The rés daqqa, an inverted "V".

(9) The dimlich, a figure which looks like a bag suspended by two strings.

daqqayeh |

The "gazelle" (ghazâl) |

The "rijl al-qatai" ("sand-grouse foot") |

the Darek |

rés daqqa |

the sâsi  the Moon |

the lâ'ibi ("doll") |

the Sun |

|

the "spindle, or spool" (dulab katân) |

the salib ("cross") |

|

the misht ("comb") |

the dimlich |

|

|

||

Refreshment had been twice dispensed, and we reached the point when we wished that our visitors would go. But they sat on. I basely forsook A. and went to my room, and when I came back, still they sat.

A. spoke in English and said to me, "They are dying to see your typewriter and have said to me, 'Do you think the khatûn would work it for us?' "

So the typewriter was produced and the young women gazed at it with awe. I typed the name of each on a piece of paper, and gave the scraps to them: and they folded them carefully. One does not see one's name printed with a machine every day in Baashika. But they still gazed.

"Does it sew also?" they asked, innocently.

As soon as they had left, I took A. up to Ras al-`Ain, for I wanted to show her the cavern, the bas-reliefs and the spring. I was a little disappointed when we reached the pool to find a procession of schoolboys marching up the path, all wearing the khaki uniform of the Government schools, and singing patriotic songs, every verse of which ended watani-" my fatherland." Very praiseworthy, no doubt, but a modern intrusion into the pagan sanctuary.

When we reached the rock, the schoolboys were perched all about it, and some had plunged into the [78] pool, but their politeness in moving away from the rock steps to let us pass and their friendly faces made me regret that I had wished them away.

After all, when we had reached the sacred cavern, it was empty. It was growing too dusk to see the panels clearly, but a smell of incense clung about the place, and when we crossed to the other side of the cave, stepping over the deep channel cut by the spring, we saw an olive-oil lamp, of the ancient shape, sending its thread of yellow flame upwards to illumine the gloom and add to the perfume of sanctity.

A schoolmaster followed us in and volunteered information about his own village, which he hoped that we would visit, offering to show us much there that would interest us. We thanked him, said good night to him and to the boys outside, and went out and down the valley in the twilight. Kids were skipping on the road, and in the village we passed women sitting at the thresholds of their courtyards, resting after the day's work, while their children played and sang.

"This is a lovely place," said A. She had fallen

in love with it, just as I had.

[79]

Chapter IX. A JACOBITE SERVICE.

"Always give altar-rites to the Gods...." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XVI.

Nature jerks the bearing-rein occasionally to remind the body that an active habit should not outrun lessened strength, and I paid in a sleepless night for too energetic a day. I lay awake and heard the wind banging to and fro the door which led to the roof, and when I crossed the courtyard to fasten it, was aware of a night-sky thick with clouds. Then heavy rain fell, the rain for which the fields were thirsting.

After breakfast A. and I determined to attend Mass at the Jacobite church, and putting on mackintoshes and taking umbrellas in hand, we picked our way along the muddy road, passing the Latin church, where we fancied those passing in gazed at us reproachfully, and then through the little graveyard, where the dead sleep under long flat slabs, into the humbler Orthodox building.

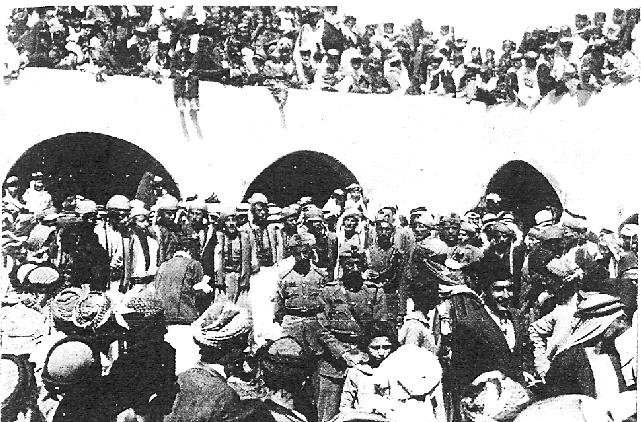

As we went through the open doorway, which was of grey Mosul marble carven by local craftsmen, a puff of incense met us, for the service was well on its way. The church was full. In front, the men sat cross-legged on the brightly-coloured mats and grass matting which covered the floor. Their heads were turbaned, their sheepskin cloaks turned inside out. Their shoes had been left on the uncovered stone paving. The women in their peasant dress squatted behind. One of them rose and, coming towards us, led us to the north side of the church, and we picked our way [80] through pairs of muddy shoes and closely packed women towards a bench, the only one, and evidently a seat of honour. Two women wearing the black, enveloping head-veil of the towns, got up politely and offered us their places upon it.

The bright Kurdish dresses, the dimness of the sanctuary, partially hidden by a marble screen and faintly illumined by candles, the grey marble columns, the swallows flying hither and thither, and keeping up their pagan twitter as they went backwards and forwards to nests somewhere in the roof of the church, the devout faces of the congregation who hung on every word of the eloquent sermon, all this formed a picture which made me feel like an intruder from another century.

The preacher, who stood at the door of the sanctuary, was none other than our friend the mutrân of Deir Matti. He held a silver cross before him as he preached, as if he were exorcising, by its magic as well as by his words, all evil from the hearts and lives of his simple congregation. He held the cross with a kerchief of magenta embroidered with silver, and his grey head was covered with the cowl embroidered with silver crosses which all monks wear. When, later on, he resumed his large bulbous black turban, this cowl hung down behind. Beneath his black robe appeared his episcopal cross, and the rose and violet of undervestments. The parish priest, elderly and bearded, wore plain black and, like his superior, the monkish cowl.

Although I could not follow all of it, the sermon was

plain and homely, and, with his presence, his fine

features and silvery beard, the mutrân looked more

than ever the minor prophet. Whenever the audience

was stirred, a murmur of assent or approval arose. At

the end of the sermon the parish priest came to the

chancel steps and, addressing the congregation, announced

that the mutrân would pay a visit to every

house and that each householder was to make him a gift

[81]

of olive-oil, soap, or grain. Money was not mentioned,

nor was there any begging or exhortation. It was an order.

The remainder stayed for the dukhrâna, that is, prayers for the benefit of the dead. These were read by the parish priest. Only a few men remained, presumably relatives of the deceased, and during the reading one man wiped his eyes repeatedly, whilst the many women who stopped at the back of the church wept and sobbed audibly, beating their knees as they squatted on the floor. Children had seated themselves on the ground by the first chancel step like a row of sparrows, and one, behaving badly, was pulled back by his father and held closely, while his companion in mischief grinned back at him.

At the conclusion of the dukhrâna all went out, including the mutrân, priest, deacons, and acolytes, and all saluted the mutrân as he passed out. A. and I entered the presbytery to pay our respects to him, A., as wife of a dignitary of the Anglican church, receiving especial honour. We were assigned seats beside the great man, who regretted that A. had not accompanied me when I visited his monastery, and expatiated on the [82] traditional hospitality of the deir extended to pilgrims of all races and faiths alike. Amongst his hearers was the young schoolmaster we had met at the cave the evening before, seated at the mutrân's right hand and beaming at the honour paid to himself and to us.

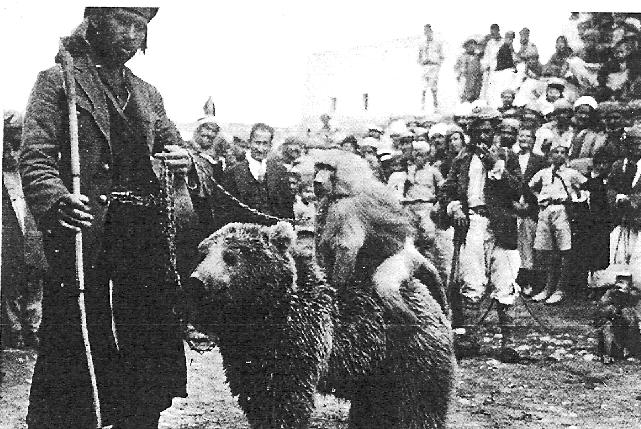

When we arrived at our house we found a great crowd gathered in the doorway. In its centre were a couple of swarthy gypsies with a pair of dancing bears and two baboons. These poor creatures performed their tricks amidst the laughter and delighted exclamations of the onlookers, amongst whom I saw the snub-nosed qawwâl, his eyes moist with merriment.

Later, I saw the black gypsy tents by Bahzané, for, in true Romany fashion, they had come for the feast and fair. Here in the Middle East, gypsies gain their living by showman-trades, by dancing, peddling, stealing, and fortune-telling, but they are needier, filthier and darker than European gypsies and are despised by tribesmen and villagers alike. Here too they have their own language, but when I took down lists of words from a kowli (gypsies are known as Kowliyah), I found few which corresponded to the Romany spoken in England. The wandering tribes think it shame either to kill them or intermarry with them, though some of the gypsy girls are handsome. The kowlis own no nationality, speak the languages of the countries through which they travel, and are expert smugglers. In the desert they neither raid nor are raided, but are often given food in return for the dancing of the women and the music or antics of the men.

Sairey, who was rapidly becoming our cross, sat long with us that Sunday, and learning that A. was childless, she came very close to me, and touching my body familiarly with her dirty hands and speaking in my ear, gave me to understand that by her manipulations she had turned many a childless wife into a rejoicing mother. Finally she went purely eldritch, invoking all the saints [83] in turn to bestow children upon A., pointing to heaven as she did so; Shaikh ‘Adi, Sitt ‘Adra (who she was I never discovered), Mar Matti, Khatuna Fakhra, and particularly, since we were Christian, "Sitt Mariam, mother of seven children." This Mariam was the martyred queen whose apparition is seen at Karakosh.

We offered her tea and gave her biscuits, which she pouched for her grandchildren, and when at long last she departed, we held council. She was fast becoming unbearable. We hated to think what those grimy hands could do to wishful and barren wives, for infection and microbes are to Sairey as devoid of meaning as the English which, to her aggravation, we talked when her presence was indefinitely prolonged. She was so unsavoury, so obstetrical, so ghoulish, so witch-like, that we both agreed that a little of her at close quarters went a long, long way. It was decided that she must be discouraged a little, as gently as possible, for we did not wish to hurt her feelings, and Jiddan, called in and the problem put before him, promised to head her off as tactfully as he could.

In the evening, A. went with Jiddan to Shaikh Mand, and returning, told me she had encountered a group of women and girls returning with skins full of milk slung from their shoulders and small black kids in their arms. With their chequered red and orange meyzars, she said, they were as brilliant as a bed of zinnias. Talking with her, they had said that in springtime their husbands and brothers stayed with the flocks on the hills day and night, and that they went up several times a day to take their men food and to get milk. They bore with them the kids and lambs, and these younglings are allowed to suck a little to start the flow before the milker presses the teats. Then they are taken back to the village, where they gambol about the house and courtyard and are as much part of the family as the children themselves.

[84] The next day the roads were still wet, for during the night there had been thunder and rain. Hearing of the poor old shaikha's fruitless visit, I thought out and wrote a better letter for her, and went to get the first from her that I might substitute the other.

We found Sitt Gulé lying outside, or rather, in the room without a third wall, like a stage, which was above the stone stairway from the courtyard, for she wanted air and peace and the living-room below was full of her sons' wives and their children. She was desperately ill. Journeying to Mosul with her fever still on her, she had become chilled, and the failure of her mission had robbed her of resistance. A quilt was spread over her restless thin body, but she was turbaned as usual, and lightly dressed in her white. She struggled up, but we persuaded her to lie and be covered. A., feeling her pulse, said that it beat fast and that her skin was dry and hot. She complained of pain between the shoulder-blades, and A., who has some experience of nursing, told me in an undertone that she feared pneumonia.

Sitt Gulé was pleased that I had written another letter, and spoke of her son upon whom her anxious mind ran unceasingly. A., practical as well as sympathetic, said that she would make her a pneumonia jacket, while I promised to try to get some quinine to combat the malaria in her blood. We were neither of us equipped with medical knowledge and there was no doctor, so we did what we could. There was a Government dispenser, we were told, in the village, but when we went to the dispensary, we found that the good man was out, visiting another village; neighbours promised, however, that they would find a lad who had charge of the key and might find the drug we required.

We then went to the sûq, the small market-place, where a few shops displayed cotton goods and groceries [85] and long paper-covered cones of cane-sugar were suspended. Here A. bought some unbleached calico of Japanese manufacture, as were most of the other materials. The next requirement was thread for sewing and cotton for the padding. The first was easily bought, but as for the cotton, it was like the vegetables, everyone grew and carded their own, or else purchased it wholesale by the sack, and the retailer had none. Jiddan suggested that the mukhtâr was sure to have some, so to the mukhtâr's house we bent our way. On the road we passed the bishop, going in state with a train of followers on his house-to-house collection spoken of in the church the day before. He looked imposing with his pastoral staff and bulbous headdress.

The mukhtâr had gone to Mosul to buy goods and fairings for the feast, but his women and children were at home, and bade us up to the reception-room, hooshing away the unkempt dog that leapt at us in the yard, barking and menacing. Up the steep, unprotected stairway we went, and our party upstairs was joined later after an immense mountaineering effort by a baby toddler about whose safety no one seemed anxious. A group of young black kids with long silky ears were playing hopscotch on the terrace.

In the guest-room mattresses were spread on the floor for us and a girl was despatched to bring some cotton. In a corner of the room stood the mukhtâr's staff, a heavy crooked stick of fragrant mahlab [mahaleb] wood which, said Jiddan, is considered sacred by Yazidis and forbidden as firewood. The seeds of the mahlab are used as spice, when pounded up, for cakes, bread, and other foods. I asked to see some, and the housemistress, lifting a bundle hung on the wall, took out packets of various spices, such as cinnamon (Arabic darsîn, Kurdish darchîn), and a large, fronded grey lichen called shahbat-al-'ajûz, which, she said, had a pleasant flavour when crushed and put into all foods. [86] Amongst the spices were mahlab seeds, and these, when I tasted them, reminded me of cloves.

The cotton was brought in a large flat basket, and

our hostess, sitting on the floor, began to beat and toss

it with a stick until A. said that for her purpose it

would do as it was. On the way down, I noticed

human hair stuffed between the stones of the walls.

I asked if this were done to protect the owner from

witchcraft. "Nakhair;" they replied. "Nay! That

is only necessary on the first night of a bride. But it

is our custom to treat hair so, lest, if it be cast out,

it be trodden underfoot."

[87]

Chapter X: LEGEND AND DOCTRINE.

"Always about his tomb the children gather in their companies, at the coming-in of the spring, and contend for the prize of kissing." -THEOCRITUS, Idyll XII.

Aisha, the pretty daughter-in-law of the Shaikha Gulé, had spoken to me several times of a shrine in the hills called Usivl Kaneri. She was the young wife of the man who had stabbed his sister, and mother of a baby son some twelve months old. To her little son she was passionately devoted, and her healthy rosy face and the baby's round one were never far apart.

The sun shone out after Sunday's rain, and we sent for Aisha, who had offered to guide us. The young woman appeared with her baby on her arm, its weight half-supported by her meyzar.

"If we are going into the hills," we said, “will not your arm ache?"

She kissed the child and assured us that since she carried him always she never felt him heavy, so we started, Aisha, A., Jiddan, the baby and its small cousin, and myself. We took the road to Ras al-'Ain, bearing to the left of the winding stream and following a mule-track cut in the rock. In the valley sounded the carefree notes of a reed-pipe: a shepherd-lad sat piping by the wayside and smiled as we paused to listen to the bird-like fluting. His pipe he had cut himself on the hills as he herded his flock. As we set up the hill the baby crowed and chuckled, and the small girl cousin gave him flowers which he crushed in his hot little fist. All the way, despite the rockiness, it was flowers, [88] flowers, flowers. Below, long strips of calico had been spread to whiten. "It comes from Yapan," said Aisha, "and is bleached by washing at the spring. While it is wet, we spread horse-manure over it for the space of a night. The next day we wash and dry it, re-washing and re-drying it in the sun many times, until it becomes as white as snow."

We went past a rock tomb, and a little farther the mule-track branched left — "the road to Shaikh ‘Adi", said Aisha. It was by this road that most pilgrims went before the days of cars to Shaikhan. Travelling by mule, a pilgrim might hope to arrive at the shrine in two days and a bit, unless stopped by brigands.

I was reminded of Acradina in Sicily at every step: by the tomb, the smell of herbs, the wild flowers, and the ancient rocky road; and Aisha herself was like a comely Syacusan maid, though her dress was far more exotic than any seen in Sicily. She was crowned by no headdress of silver coins, but wore a white turban instead. When I asked if she had one, she said with the trace of a sigh that she had sold hers for a dinâr, and I imagined that it had gone to help her husband and his family in their trouble.

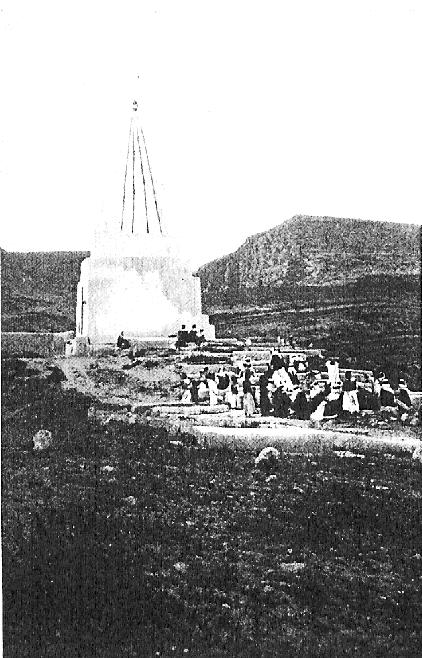

At one point in the path the cone of Melké Miran below is framed by the rocks of the gorge; it stands milky fair against the far range of blue valleys, painted, as it were, in ever fainter washes until lost against the horizon. An hour's steady mounting brought us to the head of the gorge. On one side rose the spire of the mazâr we had come to see; on the hill opposite across the gorge were ruined stone buildings. Aisha told us that they were very ancient — "perhaps two thousand years old. People (awâdim) called Gowrastan lived there. But when Muhammad came there was a battle and they were all killed and their houses cast down. They say that their blood is still to be seen upon the stones."

[89] She referred, I supposed, to the rusty-red lichen that grows on the rocks hereabout. She and I and Jiddan sat on a rock overhanging the gorge; A., full of energy and accustomed to mountain-climbing in Switzerland, strode on upwards, anxious to reach the highest point. Jiddan looked after her admiringly.

"Like a gazelle!" he murmured.

When the baby beat his mother on the chest, she readily gave him her breast, and he rested on her broad lap in perfect content, half-dreaming, half-smiling, too content to make more than a pretence of sucking. When we moved on he fell asleep, his small dimpled hand falling limp over his mother's shoulder. Wild thyme grew all about us, also a kind of sage with a balm-like fragrance, and another herb that gave out a pungent perfume like incense in the hot sun.

A. rejoined us, having had a far view from the watershed at the top, and Jiddan complimented her on her swiftness amongst the rocks. She told him that these hills were nothing compared to the Alps, to which even the snow mountains in high Kurdistan which she had seen from the top of the rock were younger sisters.

The mazâr was of the usual pattern and, as far as I could see, contained no tomb. We climbed down to the olive-garden just below us. By the spring was a cavern, maidenhair fern growing thickly in its grateful dampness, and, just as I had expected, the sacred tree by the sacred spring, this time a fig-tree, adorned with votive rags. As we had none to add to them, we tied grasses to a bough instead. Stone gutters conducted the water down to a cistern. The olives looked neglected, but it was a little paradise of green, and flowering willow grew with the figs and other trees. The rocks in this narrow apex of the gorge look like masonry, and it was difficult to persuade oneself that they had not been hewn by man. [90] On the return journey, A. borrowed Aisha's baby, who was surprised but not displeased by the change of portress, but we could not persuade them to come in to drink tea with us. Mikhail had hardly brought it in when a guest arrived, the Assyrian Presbyterian missionary, a masculine figure in plus-fours. As he drank tea, he talked well, and informed us that not only had he made a study of the Yazidi people, but had written about them in American papers.

He told us that though the villages of Baashika and Bahzané were, in a manner of speaking, a mere stone's throw from each other, the former was more progressive than the latter, thanks to the school, and that in Bahzané ancient customs were preserved which had been discontinued in Baashika.

"Your visit causes much speculation," he said smiling. "I was told that you had asked to take the photograph of a woman having a baby as you had not seen such things in your country, English babies being taken from their mothers by operation and not in the natural way."

He was chatting thus, sipping his tea and looking very Western indeed, when a second visitor arrived, this time Qawwal Sivu, the chief qawwâl. He drank tea with us, and general subjects were being discussed when the qawwâl asked what A. was sewing. When he heard that it was a bed-jacket for Sitt Gulé, he smiled and commended the deed of charity.

Thereupon, our other friend remembered, perhaps, that he was a missionary. For the qawwâl's benefit, he enlarged upon the way in which Christian charity embraced peoples of all religions and kinds, such being the command of Christ, our prophet, making A. the slightly embarrassed text of his discourse. The qawwâl, always mild and polite, received it with equanimity, although we felt a little out of countenance — which was foolish, for of course a missionary must improve the [91] shining hour like the busy bee wherever he perceives pagan honey that might be gathered into the hive of Protestant certainty.

He left us anon, the qawwâl remaining alone. We had a liking for his gentle face and diffident manner and ventured to put some questions to him. His constant reply was "How should we know? We are men, and these things are in the hand of God." It may have veiled his reluctance to answer an outsider, but it was a very pleasant veil. I asked him about their traditions concerning creation. In By Tigris and Euphrates (London, Hurst & Blackett Ltd., 1923) I related, third-hand, the story about the Pearl, the creation of Adam and the Bird, a childish fable which Siouffi relates as a Yazidi legend. He gave no such story, but answered simply that it was God who created the world, and not his angels. First there were light and darkness, then the earth, sky and stars, then the earth and its living creatures came into being, and lastly Adam and Hawa. He repeated the tale of the two jars. According to this, Hawa (Eve) claimed that children were her production and that Adam had no part in them. Adam suggested a test. He placed some of his spittle and Eve some of hers in two separate jars and kept these sealed for nine months. At the end of that period Adam opened his jar and found within a beautiful little boy and girl, whereas Eve's jar contained nothing but corruption.

He denied that Yazidis had a different descent from the rest of mankind. Asked about the fate of the soul after death, he said that the souls of the wicked go into the bodies of beasts or reptiles, that is their hell, but that for the obstinately wicked there is a hell of fire from which there is no emergence, "except," he added, "that none know what the mercy of Allah may do." The good reincarnate in human bodies after a sojourn in Paradise, but in the end of all things, if they are completely purified, they unite [92] with the supreme God, remain in bliss and return no more.

I asked why they paid such especial reverence to the Peacock Angel.

He answered, "We do not believe — like Islam," he interjected tactfully, "that He is the Lord of Evil (Sharr). He is the chief of the seven angels, and is one with Gabriel who removes the soul from the human body when Azrael comes for it. The evil in men's hearts is not from him, but from themselves."

I asked him about the reverence paid to springs and trees. He answered that they were maskûn (inhabited). We believe, he said, that there are beings, neither men nor jann [jinn]. People say that they are seen occasionally, and they call them rajul al-gheyb (or ghâib). "But," he added quickly, "who sees them? One in a thousand! Why do you ask such things? You are English, and the English know better than we do!"

As for prayer, he told me that five prayers daily are ordered for the pious Yazidi, one at dawn, one at sunrise, one at noon, one in the afternoon and one at sunset. Each time the worshipper must face the sun. Before praying, hands and face should be washed; indeed, before all worship the Yazidi should wash himself, and before any feast the body should be cleansed completely in either hot or cold water and white garments should be put on. Prayer is necessary before eating. Before and at the festivals, he said, there are especial prayers.

The missionary had already told me that Yazidi prayers are rhymed, and a mixture of Kurdish and Persian. Prayers are learnt parrot-wise, and few, if any, understand them. He did not think that they would allow me to take down any of them, as they are regarded as extremely sacred. He also had warned me that on the Thursday night of the coming feast, when the Yazidis assembled in the courtyard of Shaikh [93] Muhammad, no Christian or Moslem is permitted to be present. What they did during that night of vigil, "no one knew."

I fancied I knew what he was reluctant to hint, for

the insinuation has been made against every secret

sect in turn. The Sabaeans, Christians, and Jews have

all been variously accused in ignorance that on a certain

night of vigil they assemble in the dark, men and women,

and that shameful connection takes place in

the name of religion, none knowing who is with him

in the darkness. It is as hoary a lie as that other

about the Jews, that they eat the flesh of Christian

children at Passover.

He began by talking of the Latin Catholics. Had I seen their grand new church? Had I visited it, attended a service, seen its pictures and images? The Pope had paid for it all. "As for images, we Orthodox have none!" The henchman, more loquacious than the monk, who spoke in short sentences, inserted here, "We live by the piety of our own people: all that we have is the free gift of our own people." He went on, "The great point of difference between the Latin church and our own is Purgatory." He asked me, "Where did the Bible mention Purgatory? A good man goes to Heaven and an evil to everlasting fire, and there is an end of the matter."

[94] "But what," I asked, "of the majority, who are neither good nor bad?"

The henchman waved the irrelevant question aside, and related at length the story of Abraham's bosom and Lazarus, while the monk inquired furtively of A. if I were a Moslem?

Addressing me then, the monk informed me that he had written down many of the rhymed prayers of the Yazidis.

I praised his enterprise and said that I should be interested to see them, but he was unwilling to show them and I turned from the subject.

"You may find Yazidi priests who will answer your questions," he said, somewhat sourly, "but for money. They are not what they were formerly. There are schools and they are losing their people. Times are changed. But they are poor and will not give information for nothing."

I told him that the real purpose of my visit was merely to see the spring festival and that any other information I might gather was merely by the way.

"Humph!" said he. "Well, you will see nothing of what takes place within the shrine of Shaikh Muhammad on Thursday night. They will allow no Christian near them then. No one has seen what goes on."

He rose to go, not having eaten or drunk with us, for it was still their Lent.

After breakfast we went to Sitt Gulé's house and found her groaning in bed and still in the same comfortless spot. She was pleased with A.'s gift of the jacket, which was tied on with the help of her daughters-in-law, but the quinine, she said, had done her little good. She complained that they neglected her, and a neighbour whispered to me that there was little love lost between her and her sons' wives.

"Perhaps she will die," remarked Aisha philosophically, when we had gone below. I had been attracted [95] on a former visit by the industry of the shaikha's handmaiden, who span in a room adjoining the place where her mistress lay ill. Now they brought down the spinning-wheel and set it and the spinster in the sun, so that I might take a photograph. I gave Aisha a length of orange silk for the children's festival dresses, and this was extended to its length, and blessings called down on my head. On the previous day I had taken a similar gift to the mukhtâr's wife, as a recognition of her kindness in furnishing cotton for the bedjacket.

Sitt Gulé's handmaiden at her spinning-wheel.

A. went off with her sketching materials, and I followed her soon afterwards as far as the washing-pool at Ras al-`Ain, seating myself beside some Christian women who spread a garment for me on the grass beside them. One had her lap full of the daisy-head flowers of the camomile plant. She was picking off the stems and leaves and I helped her as we talked. An infusion of these heads, she said, is good for fever and constipation. The older woman beside her took up a handful and added, "When the flowers are dried, we put this much in a teapot and add hot water till it is as thick as honey. Then we drink it. We call this kind beybûn al-leban."

Some of the women washing clothes called out to inform me that A., "a tall woman", was farther up the valley. One said to me, "Why do you go about alone? Are you not afraid?"

"Why should I be afraid? You people of Baashika are good people."

They smiled approvingly at my answer and cried out,

"Stay with us always!"

I could only reply with a platitude. "Books are not everything and no doubt your honour's experience and wisdom are as valuable to those about you as books to younger men."

Then I consulted him about making a gift to the Yazidi poor on the occasion of the feast. To which of the men of religion should it be handed?

A humorous smile lit up his eyes and he consulted

Rashid. Perhaps, both hinted, the money would have as much

chance of reaching the poor if it were entrusted

to a responsible layman. I suggested that Rashid should

accompany me when I made the modest offering, as a witness

would ensure the distribution of the money. So eventually

it was done, and the good Qawwal Sivu to whom I handed

the money there and then divided it into smaller sums

and despatched one of his children to some of his poorer

neighbours.

. It then changed to a chorus four

times repeated of

. It then changed to a chorus four

times repeated of  with the accent on the

first beat, the whole slightly faster than the first phrase

and quickening steadily to a final crash. This appeared

to be one verse. There were four or five verses, after

which the rhythm changed abruptly to 'and-1, and-2,

and-1, and-2', i.e.

with the accent on the

first beat, the whole slightly faster than the first phrase

and quickening steadily to a final crash. This appeared

to be one verse. There were four or five verses, after

which the rhythm changed abruptly to 'and-1, and-2,

and-1, and-2', i.e.  then suddenly reverted

quickly to

then suddenly reverted

quickly to  four times repeated and getting

quicker and louder until it ended in the biggest crash

of all. This was accompanied by a flageolet descant

played on two pipes like flageolets but larger, and by

low chanting from the qawwâls in Kurdish."

four times repeated and getting

quicker and louder until it ended in the biggest crash

of all. This was accompanied by a flageolet descant

played on two pipes like flageolets but larger, and by

low chanting from the qawwâls in Kurdish."